6 minutes

Dynamic Taint Analysis and Pin

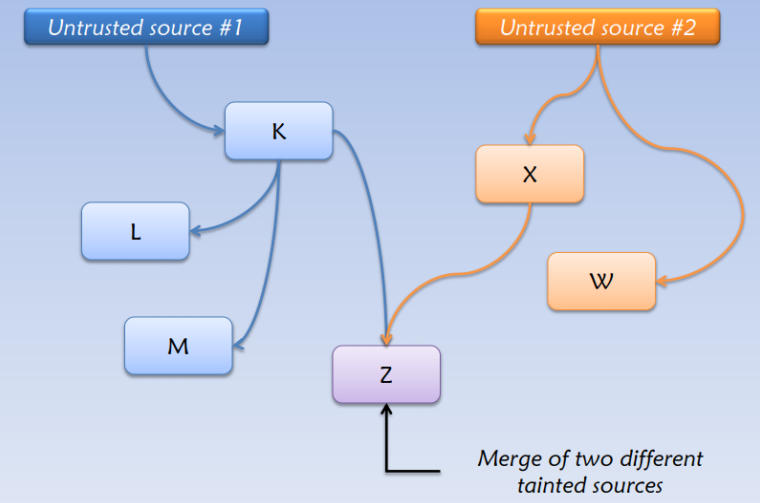

Dynamic Taint Analysis is a technique used to discover what part of memory or register are controllable by the some data we are interested, such as the user input, at a given program state. This is done by marking the interested data. There on after, any piece of data that comes in contact with the tainted data by any means, like getting computed from the tainted data, is tainted too, thus spreading the taint throughout the execution.

Taint propogration.

Taint propogration.

Regions of interest are:

- Taint Sources: Program, or memory locations, where data of interest enter the system and subsequently get tagged.

- Taint Tracking: Process of propagating data tags according to program semantics.

- Taint Sinks: Program, or memory locations, where checks for tagged data can be made.

Dynamic Taint Analysis requires a Dynamic Binary Instrumentation framework as a prerequisite. We’ll use Intel Pin.

Shadow Memory

It is the technique in which potentially every byte used by a program has a mirror byte during it’s execution. These shadow bytes can be used to record information about their original counterparts, since these bytes are invisible to the program. We create a user shadow memory to mark all the addresses that can be tainted by the data in question.

Example

We’ll need the help of a DBI to retrieve information before and after each function is called. We’ll resort to using Pin to taint user input and track it through the execution of the binary.

We’ll write a simple C++ program that reads content from a file, sends it around two functions as transfers the data into different buffers and then prints the contents onto the console. The name of the source code file is sample.cpp.

// sample.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

void foo1(char *temp, char *source){

memcpy(temp, source, strlen(source));

return;

}

void foo2(char *sink, char *temp){

memcpy(sink, temp, strlen(temp));

return ;

}

int main(int ac, char **av)

{

int fd;

char source[256], sink[256], temp[256];

fd = open("./input.txt", O_RDONLY);

read(fd, source, 256), close(fd);

foo1(temp, source);

foo2(sink, temp);

fd = open("./output.txt", O_WRONLY);

write(fd, sink, strlen(sink)), close(fd);

std::cout << sink;

return 0;

}

Create an input file named input.txt, add some content to it. Create an output file named output.txt. The source code is pretty straightforward.

Let’s write a Pintool to taint and track the input data, named tool.cpp.

// tool.cpp

#include "pin.H"

#include <asm/unistd.h>

#include <fstream>

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

/* bytes range tainted */

struct range

{

UINT64 start;

UINT64 end;

};

std::list<struct range> bytesTainted;

INT32 Usage()

{

std::cerr << "Ex 1" << std::endl;

return -1;

}

VOID ReadMem(UINT64 insAddr, std::string insDis, UINT64 memOp)

{

std::list<struct range>::iterator i;

UINT64 addr = memOp;

for(i = bytesTainted.begin(); i != bytesTainted.end(); ++i){

if (addr >= i->start && addr < i->end){

std::cout << std::hex << "[READ in " << addr << "]\t" << insAddr << ": " << insDis<< std::endl;

}

}

}

VOID WriteMem(UINT64 insAddr, std::string insDis, UINT64 memOp)

{

std::list<struct range>::iterator i;

UINT64 addr = memOp;

for(i = bytesTainted.begin(); i != bytesTainted.end(); ++i){

if (addr >= i->start && addr < i->end){

std::cout << std::hex << "[WRITE in " << addr << "]\t" << insAddr << ": " << insDis << std::endl;

}

}

}

VOID Instruction(INS ins, VOID *v)

{

if (INS_MemoryOperandIsRead(ins, 0) && INS_OperandIsReg(ins, 0)){

INS_InsertCall(

ins, IPOINT_BEFORE, (AFUNPTR)ReadMem,

IARG_ADDRINT, INS_Address(ins),

IARG_PTR, new std::string(INS_Disassemble(ins)),

IARG_MEMORYOP_EA, 0,

IARG_END);

}

else if (INS_MemoryOperandIsWritten(ins, 0)){

INS_InsertCall(

ins, IPOINT_BEFORE, (AFUNPTR)WriteMem,

IARG_ADDRINT, INS_Address(ins),

IARG_PTR, new std::string(INS_Disassemble(ins)),

IARG_MEMORYOP_EA, 0,

IARG_END);

}

}

static unsigned int lock;

#define TRICKS(){if (lock++ == 0)return;}

/* Taint from Syscalls */

VOID Syscall_entry(THREADID thread_id, CONTEXT *ctx, SYSCALL_STANDARD std, void *v)

{

struct range taint;

/* Taint from read */

if (PIN_GetSyscallNumber(ctx, std) == __NR_read){

TRICKS();

taint.start = static_cast<UINT64>((PIN_GetSyscallArgument(ctx, std, 1)));

taint.end = taint.start + static_cast<UINT64>((PIN_GetSyscallArgument(ctx, std, 2)));

bytesTainted.push_back(taint);

std::cout << "[TAINT]\t\t\tbytes tainted from " << std::hex << "0x" << taint.start << " to 0x" << taint.end << " (via read)"<< std::endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if(PIN_Init(argc, argv)){

return Usage();

}

PIN_SetSyntaxIntel();

PIN_AddSyscallEntryFunction(Syscall_entry, 0);

INS_AddInstrumentFunction(Instruction, 0);

PIN_StartProgram();

return 0;

}

Some new methods have been used. I’ll address them.

The main function, main, is responsible to get Pin ready and started.

PIN_AddSyscallEntryFunction:- Registers a function to be called immediately before execution of a system call.

The pre-syscall handler function, Syscall_entry, checks if the syscall is a read, and taints the data accordingly. Uses a list where it inserts structured entries of starting and ending addresses

PIN_GetSyscallNumber:- Retrieves the syscall number, which is then checked against the number for read.

PIN_GetSyscallArgument:- Get the value of the argument of the system call to be executed in the specified context. The change would generally be in the third argument, which is the ordinal number of the argument whose value is requested.

The instrumentation function, Instruction, cycles through all instructions and registers a callback depending on the instruction belonging to a read or write call.

INS_MemoryOperandIsRead:- Checks if memory operand memopIdx is read. It controls which memory operand to rewrite.

INS_OperandIsReg:- Checks if this operand is a register.

INS_MemoryOperandIsWritten:- Checks if memory operand memopIdx is written.

The analysis functions, ReadMem and WriteMem, simply iterates through the list of tainted addresses and prints the current instruction’s address out if it’s working with the tainted data or address. The first one checks if the accesses memory is in the tainted area, while the second one checks if the address being written to is in the tainted area.

The output is as follows.

[TAINT] bytes tainted from 0x7fffa28662e8 to 0x7fffa2866628 (via read)

[READ in 7fffa28662f0] 7f7b4c4965f4: movzx edx, byte ptr [r15+0x10]

[READ in 7fffa28662f8] 7f7b4c4966bd: movzx edi, word ptr [r15+0x18]

[READ in 7fffa2866320] 7f7b4c4966db: movzx ecx, word ptr [r15+0x40]

[READ in 7fffa2866308] 7f7b4c4966e0: mov r9, qword ptr [r15+0x28]

[READ in 7fffa2866460] 7f7b4c496741: mov rdx, qword ptr [rbx+0x20]

[READ in 7fffa2866470] 7f7b4c49674b: mov rax, qword ptr [rbx+0x30]

[READ in 7fffa2866448] 7f7b4c49675b: mov rcx, qword ptr [rbx+0x8]

[READ in 7fffa2866590] 7f7b4c4967c0: mov rax, qword ptr [r12]

[READ in 7fffa2866598] 7f7b4c4967c4: mov rcx, qword ptr [r12+0x8]

[READ in 7fffa2866470] 7f7b4c496990: mov rcx, qword ptr [rbx+0x30]

[READ in 7fffa2866590] 7f7b4c496994: mov eax, dword ptr [r12]

.

.

.

[READ in 7fffa2866558] 7f7b4c497570: mov edx, dword ptr [rbx]

[READ in 7fffa2866568] 7f7b4c4975a4: mov rdx, qword ptr [rbx+0x10]

[READ in 7fffa2866580] 7f7b4c4975b0: mov rdx, qword ptr [rbx+0x28]

[READ in 7fffa2866308] 7f7b4c497c82: mov rax, qword ptr [rdi+0x28]

[READ in 7fffa2866320] 7f7b4c497c8f: movzx edi, word ptr [rdi+0x40]

[WRITE in 7fffa2866620] 7f7b4c49921c: push rbp

[WRITE in 7fffa2866618] 7f7b4c49921d: push rbx

[TAINT] bytes tainted from 0x7fffa28662c8 to 0x7fffa2866608 (via read)

[READ in 7fffa28662d0] 7f7b4c4965f4: movzx edx, byte ptr [r15+0x10]

[READ in 7fffa28662d8] 7f7b4c4966bd: movzx edi, word ptr [r15+0x18]

[READ in 7fffa2866300] 7f7b4c4966db: movzx ecx, word ptr [r15+0x40]

[READ in 7fffa2866300] 7f7b4c4966db: movzx ecx, word ptr [r15+0x40]

[READ in 7fffa28662e8] 7f7b4c4966e0: mov r9, qword ptr [r15+0x28]

[READ in 7fffa28662e8] 7f7b4c4966e0: mov r9, qword ptr [r15+0x28]

.

.

.

[READ in 7fffa28665c8] 7f7b4c49a040: pop r13

[READ in 7fffa28665c8] 7f7b4c49a040: pop r13

[READ in 7fffa28665c8] 7f7b4c49a040: pop r13

[READ in 7fffa28665d0] 7f7b4c49a042: pop r14

[READ in 7fffa28665d0] 7f7b4c49a042: pop r14

[READ in 7fffa28665d0] 7f7b4c49a042: pop r14

[READ in 7fffa2866d20] 7f7b37d714e7: vpcmpeqb ymm1, ymm0, ymmword ptr [rdi]

And there we have all the interactions with the tainted area.

Credits for the guidance to NJU’s SECLAB “Software Security” course.