17 minutes

Source Code Instrumentation and LLVM

Source Code Instrumentation adds specific code meant for instrumentation/analysis, called Instrumentation Code, to the source files of the program under consideration. The source files are then compiled and executed. Since the instrumentation code is integrated into the binary itself, the output from the execution includes the dump of the instrumentation code which can then be used for further analysis and component testing.

Intermediate Representations

Representation of a program in a state that lies between the source code and the compiled binary(specifically, the assembly code). Compilers have a stage of intermediate code generation, where they natively generate IR of the source code.

IR is then used to emit generic assembly code allowing us to use a single universal assembler that can handle the final translation of assembly to machine code for every language. Otherwise, a full native compiler would be required for different languages and different architecture machines.

Moreover, it allows us to perform machine independent optimizations.

Let’s take a source code as an example.

while (x < 4 * y) {

x = y / 3 >> x;

if (y) print x - 3;

}

It can be expressed in different IR formats.

Structural

Graphically oriented format which is heavily used in source-to-source translations. A graph is formed showing different stages in different shapes along the flow of execution.

Semantic graph.

Semantic graph.

Linear

Pseudo-code like format with varying levels of abstraction (such as sub types of Tuples). It’s shown using simple and compact data structures and is easier to rearrange.

Tuples

Instruction-like entities consisting of an operator and zero to three arguments. Arguments can be literals, subroutine references, variables or temporaries.

// Stored form // Rendered form

(JUMP, L2) goto L2

(LABEL, L1) L1:

(SHR, 3, x, t0) t0 := 3 >> x

(DIV, y, t0, t1) t1 := y / t0

(COPY, t1, x) x := t1

(JZ, y, L3) if y == 0 goto L3

(SUB, x, 3, t2) t2 := x - 3

(PRINT, t2) print t2

(LABEL, L3) L3:

(LABEL, L2) L2:

(MUL, 4, y, t4) t4 := 4 * y

(LT, x, t4, t5) x := t4 < t5

(JNZ, t5, L1) if t5 != 0 goto L1

Generally we recognize three levels of tuple sophistication. Let’s take another source code as an example.

double a[20][10];

.

.

.

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += di)

a[i][j+2] = j;

High-level

- Keeps structure of source language program explicit.

- Source program can be reconstructed from it.

- Operands are semantic objects, including arrays and structs.

- No breaking down of array indexing computations.

- No thought of registers.

- No concern for runtime systems.

(COPY, 0, i) i := 0

(LABEL, L1) L1:

(JGE, i, n, L2) if i >= n goto L2

(INDEX, a, i, t0) t0 := a[i]

(ADD, j, 2, t1) t1 := j + 2

(INDEX, t0, t1, t2) t2 := t0[t1]

(COPY_TO_DEREF, j, t2) *t2 := j

(INCJUMP, i, di, L1) i += di, goto L1

(LABEL, L2) L2:

Medium-level

- Can be source or target oriented.

- Language and machine independent.

- Break down data structure references to deal only with simple ints and floats.

- Great for architecture-independent optimizations.

(COPY, 0, i) i := 0

(LABEL, L1) L1:

(JGE, i, n, L2) if i >= n goto L2

(MUL, i, 80, t0) t0 := i * 80

(ADD, a, t0, t1) t1 := a + t0

(ADD, j, 2, t2) t2 := j + 2

(MUL, t2, 8, t3) t3 := t2 * 8

(ADD, t1, t3, t4) t4 := t1 + t3

(COPY_TO_DEREF, j, t4) *t4 := j

(ADD, i, di, i) i := i + di

(JUMP, L1) goto L1

(LABEL, L2) L2:

Low-level

- Extremely close to machine architecture.

- Architecture dependent.

- Deviates from target language only in its inclusion of pseudo-operations and symbolic (virtual) registers.

- Intimately concerned with run-time storage management issues like stack frames and parameter passing mechanisms.

- For architecture dependent optimizations.

(LDC, 0, r0) r0 := 0

(LOAD, j, r1) r1 := j

(LOAD, n, r2) r2 := n

(LOAD, di, r3) r3 := di

(LOAD, a, r4) r4 := a

(LABEL, L1) L1:

(JGE, r0, r2, L2) if r0 >= r2 goto L2

(MUL, r0, 80, r5) r5 := r0 * 80

(ADD, r4, r5, r6) r6 := r4 + r5

(ADD, r1, 2, r7) r7 := r1 + 2

(MUL, r7, 8, r8) r8 := r7 * 8

(ADD, r6, r8, r9) r9 := r6 + r8

(TOFLOAT, r1, f0) f0 := tofloat r1

(STOREIND, f0, r9) *r9 := f0

(ADD, r0, r3, r0) r0 := r0 + r3

(JUMP, L1) goto L1

(LABEL, L2) L2:

Stack Code

Originally used for stack-based computers, and therefore use implicit names instead of explicit since explicit names take up space. It’s simple to generate and execute.

goto L2

L1:

load y

load_constant 3

load x

shr

div

store x

load y

jump_if_zero L3

load x

load_constant 3

sub

print

L3:

L2:

load x

load_constant 4

load y

mul

less_than

jump_if_not_zero L1

Three Address Code

Has a compact form with proper names, resembling a general format for most machines.

It has statements of the form:

x ← y op z, where op is any operator and (x, y, z) are names.

For example, the expression z ← x - 2 * y will be decomposed into:

t ← 2 * y

z ← x - t

and then into assembly.

load r1, y

loadI r2, 2

mult r3, r2, r1

load r4, x

sub r5, r4, r3

Hybrid

A combination of both, Graphs and Linear code.

Control Flow Graph

A graph whose nodes are basic blocks and whose edges are transitions between blocks.

A Basic Block is a:

- maximal-length sequence of instructions that will execute in its entirety.

- maximal-length straight-line code block.

- maximal-length code block with only one entry and one exit.

For example, the line code:

goto L2

L1:

t0 := 3 >> x

t1 := y / t0

x := t1

if y == 0 goto L3

t2 := x - 3

print t2

L3:

L2:

t4 := 4 * y

x := t4 < t5

if t5 != 0 goto L1

can be represented as a CFG as:

Control flow graph.

Control flow graph.

Static Single Assignment

The idea with SSA is to define each name only once in a program. This is achieved by using φ-functions, or Euler’s totient functions. These functions count positive integers upto a given integer n, that are relatively prime to n.

It can generally be found in Fortran or C compilers.

So, a pseudo-code of the form:

x ← ...

y ← ...

while (x < k)

x ← x + 1

y ← y + x

can be represented in SSA as:

x0 ← ...

y0 ← ...

if (x0 > k) goto next

loop: x1 ← φ(x0,x2)

y1 ← φ(y0,y2)

x2 ← x1 + 1

y2 ← y1 + x2

if (x2 < k) goto loop

next: ...

// φ-function will determine which out of the parameters given to us were actually used to get there. So the first time the loop is ran, x1 will have the value of x0 while all the subsequent times, x1 will have the value of x2. Similar for y1.

The primary benefit of this form is it’s ability to simultaneously simplify and improve results of various compiler optimizations just by simplifying properties of the variables.

LLVM

Low Level Virtual Machine is an IR. The main idea behind it was to get an interface to the compilation process so that optimizations to the binary could be applied then itself, rather than using JIT compilers to provide runtime optimizations. This was because these compilations by virtual machines(such as JVM) were online which meant that these optimizations had to be performed every time a certain piece of code ran. Thus, the heavy lifting task of optimization was moved from runtime to compile time.

Use the following script to setup LLVM.

Make sure you have the clang compiler installed.

git clone https://github.com/llvm/llvm-project.git

cd llvm-project

mkdir build

cd build

cmake -G "Unix Makefiles" -DLLVM_TARGETS_TO_BUILD="X86" -DLLVM_TARGET_ARCH=X86 -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE="Release" -DLLVM_BUILD_EXAMPLES=1 -DCLANG_BUILD_EXAMPLES=1 ../llvm/

cmake --build .

The LLVM IR can be displayed in two formats. Let the source code be in a file named SOURCEFILE.cpp.

- Assembly Format

- Use the tool clang to produce llvm IR.

- Run

clang++ -S -emit-llvm SOURCEFILE.cppto produce the IR by the nameSOURCEFILE.ll.

- Run

- The .ll file is the LLVM IR in assembly format. It can be directly executed using a tool called llvm-lli. It’s a JIT execution engine. Run

lli SOURCEFILE.llto execute it.

- Use the tool clang to produce llvm IR.

- Bit-code Format

- Use the tool llvm-as to produce bit-code format of the IR.

- Run

llvm-as SOURCEFILE.llto produce the bit-code file by the nameSOURCEFILE.bc.

- Run

- This assembly format of the IR can be converted into bit-code, a .bc file which is the binary format of the IR using a tool called llvm-as. Run

lli SOURCEFILE.bcto execute it. - Use the tool llvm-dis to convert bit-code format to assembly format for a given IR.

- Run

llvm-dis SOURCEFILE.bcto produce the assembly format of IR from the bit-code fileSOURCEFILE.bc.

- Run

- Use the tool llvm-as to produce bit-code format of the IR.

The tool llc, a static compiler, can then be used to convert the IR, assembly as well as bit-code format, into assembly code. Run llc SOURCEFILE.ll or llc SOURCEFILE.bc to compile the format you have into assembly code.

The tool opt, can be used to analyze and optimize the source code. It makes several passes over the code at various levels of granularity looking for opportunities to optimize it.

- Module Pass

- Single source files presented as modules.

- Call Graph Pass

- Traverses the program bottom-up.

- Function Pass

- Runs over individual functions.

- Basic Block Pass

- Runs over a basic block at a time inside the functions/routines.

- Immutable Pass

- Simply provides information about the current configuration of the compiler. Not a regular type of pass.

- Region Pass

- Executes on each single-entry-single-exit code space.

- Machine Function Pass

- Executes on the machine-dependent representation of each LLVM function.

- Loop Pass

- Focuses on one loop at a time, independent of all the other loops.

The passes can achieve either of the two goals.

- Analysis Pass

- Computes information that can be used by other passes.

- Transform Pass

- Mutates the program based on the information it has.

Let’s take a sample code to observe the difference between pass by value and pass by pointers at the IR level.

// hello.cpp

#include<stdio.h>

int add(int a, int b) {

return a+b;

}

int addptr(int* a, int* b) {

return (*a)+(*b);

}

int main(){

int a = 1, b = 2;

printf("Hello world!\n");

printf("%d\n", add(a, b));

printf("%d\n", addptr(&a, &b));

return 0;

}

We get the IR to be

; ModuleID = 'hello.cpp'

source_filename = "hello.cpp"

target datalayout = "e-m:e-p270:32:32-p271:32:32-p272:64:64-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128"

target triple = "x86_64-pc-linux-gnu"

@.str = private unnamed_addr constant [14 x i8] c"Hello world!\0A\00", align 1

@.str.1 = private unnamed_addr constant [4 x i8] c"%d\0A\00", align 1

; Function Attrs: noinline nounwind optnone sspstrong uwtable

define dso_local i32 @_Z3addii(i32 %0, i32 %1) #0 {

%3 = alloca i32, align 4

%4 = alloca i32, align 4

store i32 %0, i32* %3, align 4

store i32 %1, i32* %4, align 4

%5 = load i32, i32* %3, align 4

%6 = load i32, i32* %4, align 4

%7 = add nsw i32 %5, %6

ret i32 %7

}

; Function Attrs: noinline nounwind optnone sspstrong uwtable

define dso_local i32 @_Z6addptrPiS_(i32* %0, i32* %1) #0 {

%3 = alloca i32*, align 8

%4 = alloca i32*, align 8

store i32* %0, i32** %3, align 8

store i32* %1, i32** %4, align 8

%5 = load i32*, i32** %3, align 8

%6 = load i32, i32* %5, align 4

%7 = load i32*, i32** %4, align 8

%8 = load i32, i32* %7, align 4

%9 = add nsw i32 %6, %8

ret i32 %9

}

; Function Attrs: noinline norecurse optnone sspstrong uwtable

define dso_local i32 @main() #1 {

%1 = alloca i32, align 4

%2 = alloca i32, align 4

%3 = alloca i32, align 4

store i32 0, i32* %1, align 4

store i32 1, i32* %2, align 4

store i32 2, i32* %3, align 4

%4 = call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([14 x i8], [14 x i8]* @.str, i64 0, i64 0))

%5 = load i32, i32* %2, align 4

%6 = load i32, i32* %3, align 4

%7 = call i32 @_Z3addii(i32 %5, i32 %6)

%8 = call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([4 x i8], [4 x i8]* @.str.1, i64 0, i64 0), i32 %7)

%9 = call i32 @_Z6addptrPiS_(i32* %2, i32* %3)

%10 = call i32 (i8*, ...) @printf(i8* getelementptr inbounds ([4 x i8], [4 x i8]* @.str.1, i64 0, i64 0), i32 %9)

ret i32 0

}

declare i32 @printf(i8*, ...) #2

attributes #0 = { noinline nounwind optnone sspstrong uwtable "correctly-rounded-divide-sqrt-fp-math"="false" "disable-tail-calls"="false" "frame-pointer"="all" "less-precise-fpmad"="false" "min-legal-vector-width"="0" "no-infs-fp-math"="false" "no-jump-tables"="false" "no-nans-fp-math"="false" "no-signed-zeros-fp-math"="false" "no-trapping-math"="false" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "unsafe-fp-math"="false" "use-soft-float"="false" }

attributes #1 = { noinline norecurse optnone sspstrong uwtable "correctly-rounded-divide-sqrt-fp-math"="false" "disable-tail-calls"="false" "frame-pointer"="all" "less-precise-fpmad"="false" "min-legal-vector-width"="0" "no-infs-fp-math"="false" "no-jump-tables"="false" "no-nans-fp-math"="false" "no-signed-zeros-fp-math"="false" "no-trapping-math"="false" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "unsafe-fp-math"="false" "use-soft-float"="false" }

attributes #2 = { "correctly-rounded-divide-sqrt-fp-math"="false" "disable-tail-calls"="false" "frame-pointer"="all" "less-precise-fpmad"="false" "no-infs-fp-math"="false" "no-nans-fp-math"="false" "no-signed-zeros-fp-math"="false" "no-trapping-math"="false" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "unsafe-fp-math"="false" "use-soft-float"="false" }

!llvm.module.flags = !{!0, !1, !2}

!llvm.ident = !{!3}

!0 = !{i32 1, !"wchar_size", i32 4}

!1 = !{i32 7, !"PIC Level", i32 2}

!2 = !{i32 7, !"PIE Level", i32 2}

!3 = !{!"clang version 10.0.0 "}

The bitcode comes out gibberish, as expected, so I’m not going to show the output of that here.

Focusing on the IR of the source and ignoring all the meta data, we can see that an almost C like, straight up readable.

The main function exists right in the middle of the output.

- Defined with a return type

i32, which is quite clearly, a 32-bit int. It’s not used much, except as the return values of system calls such asprintf,scanfandmain. - The

allocainstruction allocated memory on the stack, with an align parameter to align the allocation on a boundary. - The

getelementptrinstruction gets the address of a subelement of an aggregates data structure(such as arrays and structs). It just calculates the address, which is then passed on as parameters to function calls.

We can see three function calls, two to printf and one to _Z3addii. The first one is pretty clear but the second one seems like the name we used in the source code has been morphed. It has undergone mangling by the compiler. Name Mangling is the process of adding additional information to the name of a function so as to make sure two separate functions do not end up having the same name in the same namespace, causing a conflict. It’s only done when two functions with same name exist when a C source file is being compiled, but it’s always applied when a C++ source file is being compiled.

The add function we defined isn’t that complicated either. It performs pass by value.

- Uses the

allocainstruction to allocate stack space for two integers. - Uses the

storeinstruction to map the value of the parameters we passed to the function onto the memory freshly allocated. - The

i32*s are the references( to the integers. - Uses the load instruction to load the value of the parameters from the memory into local variables.

- Uses the

add nswinstruction to add the two variables with a No Signed Wrap property(signed integers won’t be wrapped around in case of an overflow during arithmetic operation).

The addptr function performs pass by pointers.

- Same as before mostly except the extra instructions because of the use of pointers. The variables get the references to the arguments(which are addresses) passed.

- These variables are then stored onto the stack.

- The

i32**s are the addresses. - The four load instructions can be seen to dereferences values stored at the given addresses into integer variables.

- The addition is then performed on these integers and the result returned.

Instrumentation

We’ll create a simple C++ program to instrument.

Since printing statements is a cliché now, we’ll do something different. Let’s find loops and predict their number of iterations. It’s a rudimentary approach full of loop holes, but works for naïve programs.

// loop.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int looper0(int low, int high) {

int i, sum = 0;

for(i = low; i < high; i++)

sum += i;

return sum;

}

int looper1(int low, int high) {

int i, sum = 0;

for(i = low; i < high; i++)

sum += i;

return sum;

}

int main()

{

int sum;

sum = looper0(0, 250);

sum += looper1(0, 250);

sum += looper0(0, 250);

std::cout<<sum<<endl;

return 0;

}

Compile the file to IR by executing clang++ -S -emit-llvm loop.cpp.

Make a directory named CUSTOM_DIR inside PATH/llvm-project/llvm/lib/Transforms/, where PATH is the path of the folder where LLVM repository was cloned.

Let’s write a function pass to collect the target stats. Make a file inside the newly formed folder. Let’s say it’s named CUSTOM_PASS.cpp.

// CUSTOM_PASS.cpp

// PART 1

#include "llvm/IR/Function.h"

#include "llvm/Pass.h"

#include "llvm/Support/raw_ostream.h"

// PART 2

using namespace llvm;

namespace {

// PART 3

struct PASS_NAME : public FunctionPass {

// PART 4

static char ID; // Pass identification, replacement for typeid

PASS_NAME() : FunctionPass(ID) {}

// PART 5

bool runOnFunction(Function &F) override {

unsigned int basicBlockCount = 0;

unsigned int instructionCount = 0;

for(BasicBlock &bb : F) {

++basicBlockCount;

for(Instruction &i: bb){

++instructionCount;

}

}

errs() << "Function Name: ";

errs().write_escaped(F.getName()) << "\n " << "Basic Blocks: " << basicBlockCount

<< "\n " << "Instructions: " << instructionCount << "\n";

return false;

}

};

}

// PART 6

char PASS_NAME::ID = 0;

// PART 7

static RegisterPass<PASS_NAME> X("PASS_NAME", "Custom Pass");

- PART 1: The include statements. We include those particular header files because we’re writing a Pass, on each Function, and we’ll be printing the stats.

- PART 2: Declares the namespace. It is necessary since everything defined in the header files are in the llvm namespace. And then we start with an anonymous namespace block.

- PART 3: Declares our pass named PASS_NAME. Declares a subclass for the parent class named FunctionPass, which operates on every function defined.

- PART 4: Declares a unique pass identifier which is used by LLVM to identify the pass.

- PART 5: We overwrite the runOnFunction method from the parent class and write our code for instrumentation. The return value is the answer to the question “Does this code modify the original source code?”. If it does, return true, else return false.

- PART 6: The ID to our pass PASS_NAME is initialized.

- PART 7: Register the subclass we just created. The first argument is the name of the parameter we will provide to choose this pass, and the second argument is the name of the pass.

Add a file named CMakeLists.txt to the same folder with the following content.

add_llvm_library( LLVMCUSTOM_PASS MODULE

CUSTOM_PASS.cpp

PLUGIN_TOOL

opt

)

The name LLVMCustomPass is the name of the module(shared object) that will be created on ‘making’ it, should be changed as wanted.

The name CustomPass.cpp is the name of the source code file, should be changed according to what the name of the source file for your pass is.

Add this folder to the PATH/llvm-project/llvm/lib/Transforms/CMakeLists.txt, that is, the CMakeLists.txt file that exists in our newly created directory’s parent directory. This ensures that our new directory will be taken into account while building the binaries and the libraries next time.

add_subdirectory(CUSTOM_DIR)

Then run make from PATH/llvm-project/build/.

You’ll see that a new file, PATH/llvm-project/build/lib/LLVMCUSTOM_PASS.so has been created. This is the module we’ll use to instrument our target source code.

Run PATH/llvm-project/llvm/build/bin/opt -load PATH/llvm-project/build/lib/LLVMCUSTOM_PASS.so -PASS_NAME < loop.ll to see the output from the instrumentation.

PATH/llvm-project/llvm/build/bin/optcalls the aforementioned opt tool.- -load is the parameter to provide the instrumentation module.

PATH/llvm-project/build/lib/LLVMCUSTOM_PASS.sois the instrumentation module we built.-PASS_NAMEis passed to ascertain the particular pass to be used.<is used to redirect input from a file.loop.llis the file with the assembly formatted IR.

The output from the instrumentation module is as follows.

Function Name: __cxx_global_var_init

Basic Blocks: 1

Instructions: 3

Function Name: _Z7looper0ii

Basic Blocks: 5

Instructions: 25

Function Name: _Z7looper1ii

Basic Blocks: 5

Instructions: 25

Function Name: main

Basic Blocks: 1

Instructions: 17

Function Name: _GLOBAL__sub_I_calc.cpp

Basic Blocks: 1

Instructions: 2

And there we go. We get our stats on the basic blocks and instructions that exist in the IR assembly.

To verify, we’ll have to take a look at the call graphs of the functions.

To generate the CFGs, run PATH/llvm-project/llvm/build/bin/opt -dot-cfg loop.bc. This will generate multiple dot files by the name of the functions. Use a utility like xdot or dotty to view them.

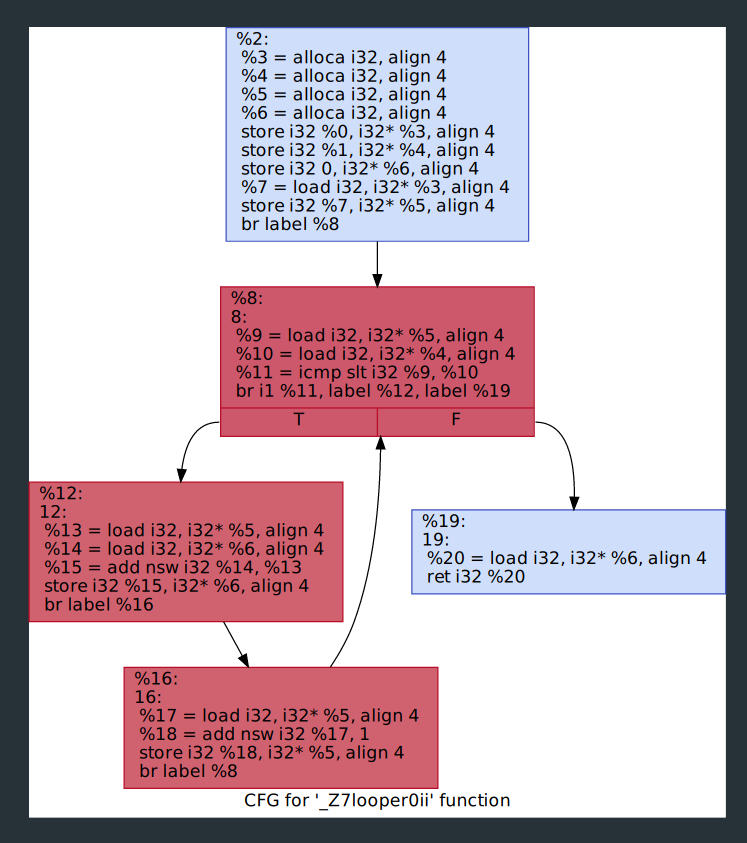

As an example, let’s checkout the CFG for the function _Z7looper0ii.

CFG for the looper0 function.

CFG for the looper0 function.

Counting the number of basic blocks and instructions, the output from our instrumentation checks out.

Credits for the guidance to Mike Shah’s talk “Intro to LLVM” at FOSDEM 18.