13 minutes

Principles of Symbolic Execution

Symbolic Execution, or symbex, is a software analysis technique that expresses program state in terms of logical formulas that you can automatically reason about to answer complex questions about a program’s behavior. Can automatically increase the code coverage of dynamic analyses by generating new inputs that lead to unexplored program paths. Apply it sparingly and carefully because of scalability issues.

- Symbex executes (or emulates) an application with symbolic values.

- Symbolic values represent a domain covering possible concrete values, represented by symbols like φ.

- Symbolic variables are just memory addresses that will hold symbolic values.

- Symbolic execution computes logical formulas over these symbols. These formulas represent the operations performed on the symbols during execution and describe limits for the range of values the symbols can represent.

- Many symbex engines maintain the symbols and formulas as metadata in addition to concrete values rather than replacing the concrete values.

- The collection of symbolic values and formulas that a symbex engine maintains is called the Symbolic State.

- Symbex engine computes two different kinds of formulas over these symbolic values: a set of symbolic expressions and a path constraint.

Symbolic Expressions

A symbolic expression (φj , with j ∈ N) corresponds either to a symbolic value αi or to some mathematical combination of symbolic expressions, such as φ3 = φ1 + φ2.

- Symbolic Expression Store (σ) is the set of all the symbolic expressions used in the symbolic execution.

- Symbex maintains a mapping of variables (or in the case of binary symbex, registers and memory locations) to symbolic expression.

- I refer to the combination of the path constraint and all symbolic expressions and mappings as the symbolic state.

Various notations for a symbolic expression e are as follows:

- m - symbolic variable

- c - constant

- *(e, e’) - multiplication

- ≤(e, e’) - comparison

- ¬e’ - negation

- *e’ - pointer dereference and more.

Symbolic variables of an expression e are the set of addresses m that occur in it.

Path Constraint

A path constraint (π) encodes the limitations imposed on the symbolic expressions by the branches taken during execution. For instance, if the symbolic execution takes a branch if(x < 5) and then another branch if(y >= 4), where x and y are mapped to the symbolic expressions φ1 and φ2, respectively, the path constraint formula becomes φ1 < 5 ∧ φ2 ≥ 4.

- Path constraints are sometimes referred to as Branch Constraints.

A solution (possible concrete values) to a constraint which can lead the concrete execution of the program to the desired point is called a model. Models are computed automatically with a special program called a constraint solver, which is capable of solving for the symbolic values such that all constraints and symbolic expressions are satisfied. In some cases, the solver might also report that no solution exists, meaning that the path is unreachable. In general, it’s not feasible to cover all paths through a nontrivial program since the number of possible paths increases exponentially with the number of branches.

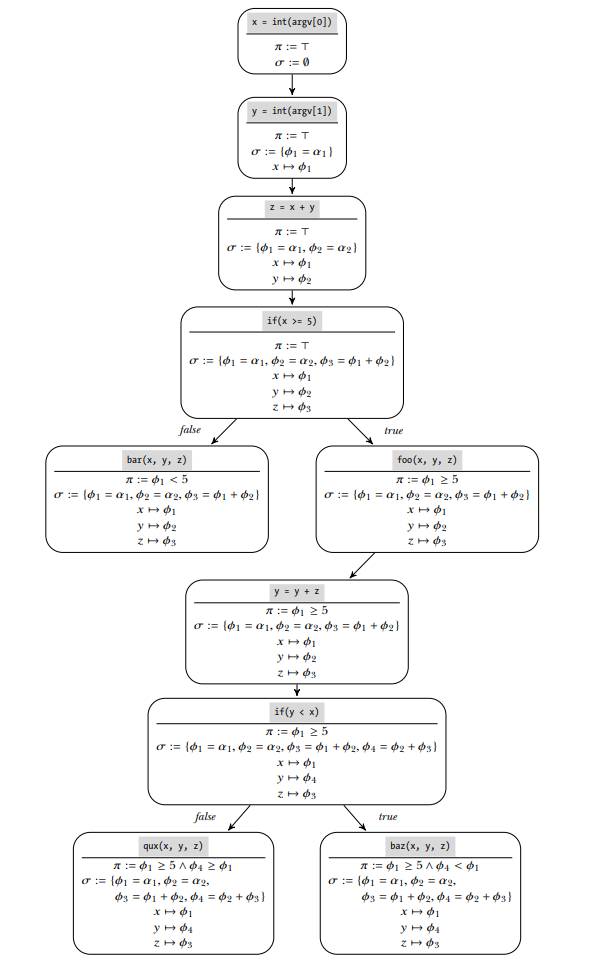

Path constraints and symbolic state for all paths in the example function.

Path constraints and symbolic state for all paths in the example function.

➊ x := int(argv[0]), y := int(argv[1])

➋ z := x + y

➌ if x >= 5:

foo(x, y, z)

y := y + z

if y < x: baz(x, y, z)

else: qux(x, y, z)

➍ else: bar(x, y, z)

Step ➊ is reading x and y from user input.

- The path constraint π is initially set to T(tautology). This shows that no branches have yet been executed, so no constraints are imposed.

- Symbolic expression store σ is initially the empty set. After reading x, the symbex engine creates a new symbolic expression φ1 = α1, which corresponds to an unconstrained symbolic value that can represent any concrete value, and maps x to that expression. Reading y causes an analogous effect, mapping y to φ2 = α2.

Step ➋ is computing z = x + y.

- The symbex engine maps z to a new symbolic expression φ3 = φ1 + φ2.

Step ➌ checks conditional if(x >= 5).

- The engine adds the branch constraint φ1 ≥ 5 to π and continues the symbolic execution at the branch target, which is the call to foo.

- Because you’ve now reached a call to foo, you can solve the expressions and branch constraints to find concrete values for x and y that lead to this foo invocation.

- x and y map to the symbolic expressions φ1 = α1 and φ2 = α2, respectively, where α1 and α2 are the only symbolic values.

- Only one branch constraint exists: φ1 ≥ 5.

- Thus, a possible model to reach this call to foo is α1 = 5 ∧ α2 = 0.

- α2 could take any value because it doesn’t occur in any of the symbolic expressions that appear in the path constraint.

Step ➍ takes the else case.

- To reach the call to bar instead, avoid the if(x >= 5) branch by changing the path constraint φ1 ≥ 5 to φ1 < 5 and ask the constraint solver for a new model.

- Thus, a possible model would be α1 = 4 ∧ α2 = 0.

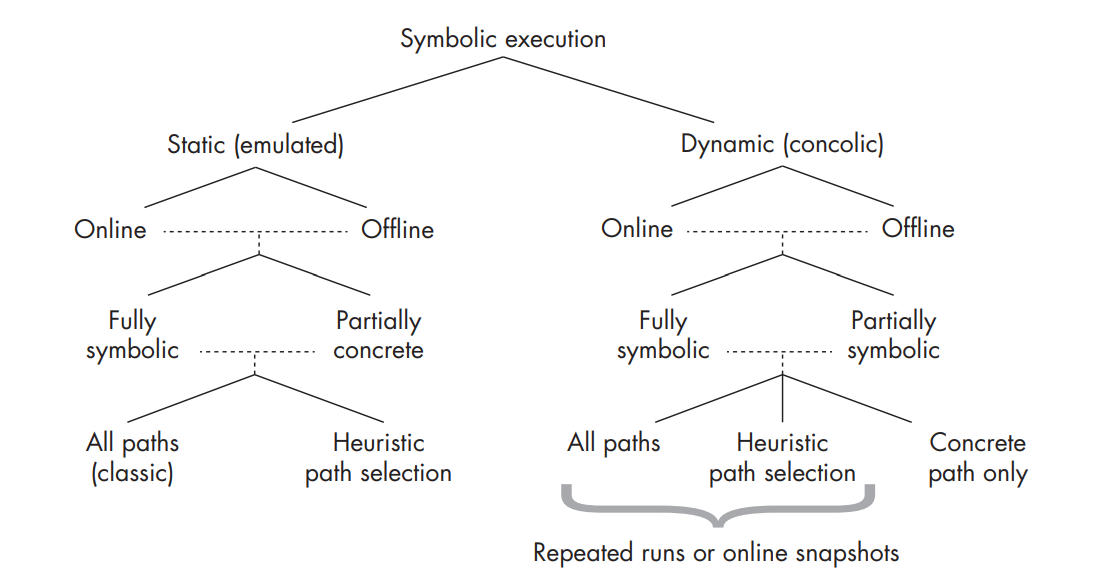

Variants

Symbolic execution design dimensions.

Symbolic execution design dimensions.

Static Symbolic Execution (SSE)

- Emulates part of a program, propagating symbolic state with each emulated instruction.

- Either analyzes all possible paths exhaustively or uses heuristics to decide which paths to traverse.

- Allows analyzing programs that can’t run on the system CPU, like analyzing ARM binaries on x86.

- Exploring both directions at every branch isn’t always possible because of scalability issues.

- While heuristics can be used to limit the number of explored branches, it’s non-trivial to come up with effective heuristics that capture all the interesting paths.

- Forks off a new symbex instance at each branch to explore both directions in parallel.

- Parts of an application’s behavior can be hard to model correctly with SSE, specifically when control flows outside the application to software components that the symbolic execution engine doesn’t control, such as the kernel or a library. Happens when a program issues a system call or library call, receives a signal, tries to read an environment variable, and so on.

Effect Modeling

Models the effects of external interactions like system calls and library calls. These models are a sort of “summary” of the effects that a system or library call has on the symbolic state. Performance-wise, effect modeling is a relatively cheap solution. However, creating accurate models for all possible environment interactions—including with the network, the filesystem, and other processes—is a monumental task, which may involve creating a simulated symbolic filesystem, symbolic network stack, and so on. To make matters worse, the models have to be rewritten to simulate a different operating system or kernel. Models are therefore often incomplete or inaccurate in practice.

Direct External Interactions

Instead of modeling the effects of a system call, the symbex engine may actually make the system call and incorporate the concrete return value and side effects into the symbolic state. Leads to problems when multiple paths that perform competing external interactions are explored in parallel. For instance, if multiple paths operate on the same physical file in parallel, this may lead to consistency issues if the changes conflict. Can be resolved by cloning the complete system state for each explored path, but that solution is extremely memory intensive. Moreover, because external software components cannot handle symbolic state, interacting directly with the environment means an expensive call to the constraint solver to compute suitable concrete values that can be passed to the system or library call that is being invoked.

Dynamic Symbolic Execution (DSE)

Known as Concolic Execution, as in “concrete symbolic execution” because this approach uses concrete state to drive the execution while maintaining symbolic state as metadata.

- Runs only one path at once, as determined by the concrete inputs. To explore different paths, it “flips” the path constraints and then uses the constraint solver to compute concrete inputs that lead to the alternative branch. These concrete inputs can be used to start a new concolic execution that explores the alternative path.

- Much more scalable since it doesn’t maintain multiple parallel execution states.

- External interactions are run concretely. This doesn’t lead to consistency issues because concolic execution doesn’t run different paths in parallel.

- Constraints it computes tend to involve fewer variables since it runs only a part at a time, making the constraints easier and far faster to solve.

- Code coverage achieved by concolic execution depends on the initial concrete inputs. Since concolic execution “flips” only a small number of branch constraints at once, it can take a long time to reach interesting paths if these are separated by many flips from the initial path.

- Less trivial to symbolically execute only part of a program, although it can be implemented by dynamically enabling or disabling the symbolic engine at runtime.

Online vs. Offline

Symbex engines that explore multiple program paths in parallel are called online, while engines that explore only one path at a time are called offline.

- Online symbex doesn’t execute the same instruction multiple times, thus making it efficient but making it memory-intensive to keep track of all states in parallel. In contrast, offline implementations often analyze the same chunk of code multiple times, having to run the entire program from the start for every program path.

- Offline symbex attempt to keep the memory overhead to a minimum by merging identical parts of program states together, splitting them only when they diverge. This optimization is known as copy on write because it copies merged states when a write causes them to diverge, creating a fresh private copy of the state for the path issuing the write.

Symbolic State

Engines provide the option of omitting symbolic state for some registers and memory locations.

- By tracking symbolic information only for the selected state while keeping the rest of the state concrete, size of the state and the complexity of the path constraints and symbolic expressions can be reduced. This approach is more memory efficient and faster because the constraints are easier to solve.

- The trade-off is choosing which state to make symbolic and which to make concrete only, and this decision is not always trivial. Choosing incorrectly may cause the symbex tool to report unexpected results.

- Pointers can be symbolic, meaning that their value is not concrete but partly undetermined. This introduces a difficult problem when memory loads or stores use a symbolic address.

Fully Symbolic Memory

Solutions based on fully symbolic memory attempt to model all the possible outcomes of a memory load or store operation, forking the state into multiple copies to reflect each possible outcome of the memory operation. For instance, let’s suppose we’re reading from an array a using a symbolic index φi , with the constraint that φi < 5. The state-forking approach would then fork the state into five copies: one for the situation where φi = 0 (so that a[0] is read), another one for φi = 1, and so on. Another way to achieve the same effect is to use constraints with if-then-else expressions supported by some constraint solvers. These expressions are analogous to if-then-else conditionals used in programming languages. In this approach, the same array read is modeled as a conditional constraint that evaluates to the symbolic expression of a[i] if φi = i. This approach suffers from state explosion or extremely complicated constraints if any memory accesses use unbounded addresses. These problems are more prevalent in binary-level symbex than source-level symbex because bounds information is not readily available in binaries.

Address Concretization

To avoid the state explosion of fully symbolic memory, unbounded symbolic addresses can be replaced with concrete ones.

- In concolic execution, the symbex engine can simply use the real concrete address.

- In static symbolic execution, the engine will have to use a heuristic to decide on a suitable concrete address.

It reduces the state space and complexity of constraints considerably, but the downside is that it doesn’t fully capture all possible program behaviors, which may lead the symbex engine to miss some possible outcomes.

Path Coverage

Classic symbolic execution explores all program paths, forking off a new symbolic state at every branch. This approach doesn’t scale because the number of possible paths increases exponentially with the number of branches in the program; this is the well-known path explosion problem. In fact, the number of paths may be infinite if there are unbounded loops or recursive calls. For nontrivial programs, a different approach is required, such as using heuristics to decide which paths to explore.

- A common heuristic is DFS (Depth-First Search), which explores one complete program path entirely before moving on to another path, under the assumption that deeply nested code is likely more “interesting” than superficial code.

- BFS (Breadth-First Search) does the opposite, exploring all paths in parallel but taking longer to reach deeply nested code.

Concolic execution explores only one path at a time as driven by concrete inputs, but can also be combined with the heuristic path exploration approach or even with the approach of exploring all paths. The easiest way to explore multiple paths is to run the application repeatedly, each time with new inputs discovered by “flipping” branch constraints in the previous run. A more sophisticated approach is to take snapshots of the program state so that after exploring one path, the snapshot can restore the state to an earlier point in the execution and explore another path from there.

Optimisation

Simplifying Constraints

Simplifying constraints as much as possible to keep usage of the constraint solver to an absolute minimum can reduce computation extensively since constraint solving is the most computationally expensive aspect of symbex. Thus, aim to reduce the complexity of the constraint solver’s task, thereby speeding up the symbolic execution, without significantly affecting the accuracy of the analysis.

Limiting the Number of Symbolic Variables

Simplifying constraints reduces the number of symbolic variables and make the rest of the program state concrete only. However, randomly concretizing state may result in wrong state to be concretized causing your symbex tool to miss possible solutions to the problem. Using a pre-processing pass that employs taint analysis and fuzzing to find inputs that cause dangerous effects, such as a corrupted return address, and then using symbex to find out whether there are any inputs that corrupt that return address such that it allows exploitation, can save a lot of computation. Using relatively cheap techniques such as DTA and fuzzing to find out whether there’s a potential vulnerability and using symbolic execution only in potentially vulnerable program paths to find out how to exploit that vulnerability in practice is a much more efficient approach.

Limiting the Number of Symbolic Operations

Symbolically execute only those instructions that are relevant. For instance, exploiting an indirect call through the rax register involve focusing on only the instructions that contribute to rax’s value. Thus, computing a backward slice to find the instructions contributing to rax and then symbolically emulating the instructions in the slice reduces number of symbolic operations in contrast to emulating all instructions.

Simplifying Symbolic Memory

Full symbolic memory can cause an explosion in the number of states or the size of the constraints if there are any unbounded symbolic memory accesses. Impact of such memory accesses on constraint complexity can be reduced by concretizing them.

Avoiding the Constraint Solver

There are practical ways to limit the need for constraint solving in symbex tools, such as using pre-processing passes to find potentially interesting paths and inputs to explore with symbex and pinpoint the instructions affected by these inputs. This helps in avoiding needless constraint solver invocations for uninteresting paths or instructions. Symbex engines and constraint solvers may also cache the results of previously evaluated (sub)formulas, thereby avoiding the need to solve the same formula twice.

Citation: Practical Binary Analysis.