23 minutes

Set 3

Refer to this repository for solution scripts and the IPython Notebook pertaining to the explanations here.

Challenge 17: The CBC padding oracle

This is the best-known attack on modern block-cipher cryptography.

Combine your padding code and your CBC code to write two functions.

The first function should select at random one of the following 10 strings:

MDAwMDAwTm93IHRoYXQgdGhlIHBhcnR5IGlzIGp1bXBpbmc=

MDAwMDAxV2l0aCB0aGUgYmFzcyBraWNrZWQgaW4gYW5kIHRoZSBWZWdhJ3MgYXJlIHB1bXBpbic=

MDAwMDAyUXVpY2sgdG8gdGhlIHBvaW50LCB0byB0aGUgcG9pbnQsIG5vIGZha2luZw==

MDAwMDAzQ29va2luZyBNQydzIGxpa2UgYSBwb3VuZCBvZiBiYWNvbg==

MDAwMDA0QnVybmluZyAnZW0sIGlmIHlvdSBhaW4ndCBxdWljayBhbmQgbmltYmxl

MDAwMDA1SSBnbyBjcmF6eSB3aGVuIEkgaGVhciBhIGN5bWJhbA==

MDAwMDA2QW5kIGEgaGlnaCBoYXQgd2l0aCBhIHNvdXBlZCB1cCB0ZW1wbw==

MDAwMDA3SSdtIG9uIGEgcm9sbCwgaXQncyB0aW1lIHRvIGdvIHNvbG8=

MDAwMDA4b2xsaW4nIGluIG15IGZpdmUgcG9pbnQgb2g=

MDAwMDA5aXRoIG15IHJhZy10b3AgZG93biBzbyBteSBoYWlyIGNhbiBibG93

… generate a random AES key (which it should save for all future encryptions), pad the string out to the 16-byte AES block size and CBC-encrypt it under that key, providing the caller the ciphertext and IV.

The second function should consume the ciphertext produced by the first function, decrypt it, check its padding, and return true or false depending on whether the padding is valid.

It turns out that it’s possible to decrypt the ciphertexts provided by the first function.

The decryption here depends on a side-channel leak by the decryption function. The leak is the error message that the padding is valid or not.

You can find 100 web pages on how this attack works, so I won’t re-explain it. What I’ll say is this:

The fundamental insight behind this attack is that the byte 01h is valid padding, and occur in 1/256 trials of “randomized” plaintexts produced by decrypting a tampered ciphertext.

02h in isolation is not valid padding.

02h 02h is valid padding, but is much less likely to occur randomly than 01h.

03h 03h 03h is even less likely.

So you can assume that if you corrupt a decryption AND it had valid padding, you know what that padding byte is.

It is easy to get tripped up on the fact that CBC plaintexts are “padded”. Padding oracles have nothing to do with the actual padding on a CBC plaintext. It’s an attack that targets a specific bit of code that handles decryption. You can mount a padding oracle on any CBC block, whether it’s padded or not.

# Imports

import os

import base64

import random

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

# Given

b64_strings = [

b'MDAwMDAwTm93IHRoYXQgdGhlIHBhcnR5IGlzIGp1bXBpbmc=',

b'MDAwMDAxV2l0aCB0aGUgYmFzcyBraWNrZWQgaW4gYW5kIHRoZSBWZWdhJ3MgYXJlIHB1bXBpbic=',

b'MDAwMDAyUXVpY2sgdG8gdGhlIHBvaW50LCB0byB0aGUgcG9pbnQsIG5vIGZha2luZw==',

b'MDAwMDAzQ29va2luZyBNQydzIGxpa2UgYSBwb3VuZCBvZiBiYWNvbg==',

b'MDAwMDA0QnVybmluZyAnZW0sIGlmIHlvdSBhaW4ndCBxdWljayBhbmQgbmltYmxl',

b'MDAwMDA1SSBnbyBjcmF6eSB3aGVuIEkgaGVhciBhIGN5bWJhbA==',

b'MDAwMDA2QW5kIGEgaGlnaCBoYXQgd2l0aCBhIHNvdXBlZCB1cCB0ZW1wbw==',

b'MDAwMDA3SSdtIG9uIGEgcm9sbCwgaXQncyB0aW1lIHRvIGdvIHNvbG8=',

b'MDAwMDA4b2xsaW4nIGluIG15IGZpdmUgcG9pbnQgb2g=',

b'MDAwMDA5aXRoIG15IHJhZy10b3AgZG93biBzbyBteSBoYWlyIGNhbiBibG93',

]

The first function:

- Selects a random base64 encoded given string.

- Pad the string to block size.

- CBC encrypts the chosen string under the key.

def encryptor(IV: bytes, key: bytes) -> (bytes, bytes):

"""

Chose a random base64 encoded string and encrypt via AES CBC Mode.

"""

index = random.randint(0, len(b64_strings)-1)

selected_string = b64_strings[index]

ciphertext = AES_CBC_encrypt(selected_string, IV, key)

return selected_string, ciphertext

The second function:

- Decrypts the given ciphertext.

- Verify the decrypted string’s padding.

- Returns true or false based on validity of padding.

NOTE: The specifications of this function are to be paid attention to, specifically the last one. The attack is only possible if the oracle gives a feedback on the padding of the plaintext encrypted being valid.

def decryptor(ciphertext: bytes, IV: bytes, key: bytes) -> bool:

"""

Decrypt the given ciphertext via AES CBC Mode and check if padding is valid.

"""

plaintext = AES_CBC_decrypt(ciphertext, IV, key)

if PKCS7_padded(plaintext):

return True

else:

return False

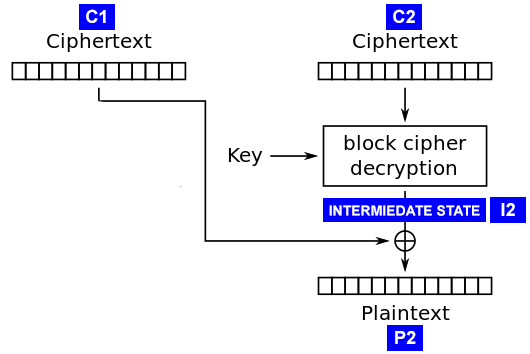

AES CBC Decryption.

AES CBC Decryption.

The philosophy for the padding attack stems from the design of the CBC encryption mechanism. The ciphertext from the previous block is xored with the intermediate state of the next block formed during it’s decryption. Since we have control over the ciphertext, maybe we can manipulate the blocks in some way into giving us some sort of indication towards it’s effectiveness.

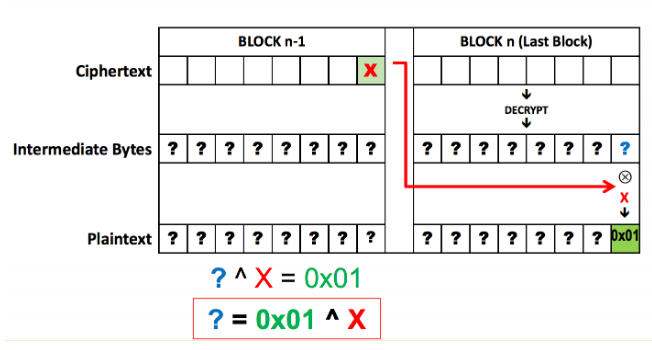

Xoring the bytes to get valid padding.

Xoring the bytes to get valid padding.

The idea of the padding oracle attack is as follows:

We want to modify the last byte X of the second-to-last block so that the CBC decryption of the last block which has ? as its content yields 0x01 instead. This of course works because CBC decrypts as:

Mⁱ = Decrypt(Cⁱ) ⊕ Cⁱᐨ¹

Finding the right X is achieved by querying all 256 values to the padding oracle to which you should only get one positive response (when you hit the correct plaintext guess or accidently hit a longer padding).

When we’ve guessed this byte and move on to the next byte, the byte in focus can be deciphered the same way, while the byte we already discovered(the last byte of the block) can be xored with a value that converts the last byte of the plaintext in line with the requirement (say, we decipher the last byte as ‘A’, and since it’s the second last byte in focus, we have to convert it into ‘\x02’. We simply put in the last byte of the previous block as something that would give us the plaintext’s last byte’s value to be ‘\x02’ after all the xoring.

The execution of the attack is in two parts, the first part being the modification of the previous cipher block and the second being the brute forcing, and are complimentary to each other.

Part 1:

We create a function to modify the (i-1)th cipherblock according to what the value of the padding byte has to be. The block to be modified is provided(treated as the IV) along with the plaintext already deciphered, padding of length we’re at(gives away the index of the byte we’re guessing, since we have to get the padding valid for the number of bytes guessed correctly already + 1) and of course, the byte we think is the one for us(the guessed byte).

The block is modified as follows:

- The IV remains as is until (length of the block - padding length). This is because these bytes aren’t the focus yet, and could have any value for that matter.

- We then add our guessed byte. This is the one we think will get us the right padding.

- Followed by appending the bytes that would definitely generate the bytes corresponding to the padding length, since a block requiring a padding of N bytes is padding with the byte ‘\xN’ ( following the norms of PKCS7).

def modify_block(IV: bytes, guessed_byte: bytes, padding_len: int, found_plaintext: bytes) -> bytes:

"""

Creates a forced block of the ciphertext, ideally to be given as IV to decrypt the following block.

The forced IV will be used for the attack on the padding oracle CBC encryption.

"""

block_size = len(IV)

# Get the index of the first character of the padding.

index_of_forced_char = len(IV) - padding_len

# Using the guessed byte given as input, try to force the first character of the

# padding to be equal to the length of the padding itself.

forced_character = IV[index_of_forced_char] ^ guessed_byte ^ padding_len

# Form the forced ciphertext by adding to it the forced character...

output = IV[:index_of_forced_char] + bytes([forced_character])

# ...and the characters that were forced before (for which we already know the plaintext).

m = 0

for k in range(block_size - padding_len + 1, block_size):

# Force each of the following characters of the IV so that the matching characters in

# the following block will be decrypted to "padding_len".

forced_character = IV[k] ^ ord(found_plaintext[m]) ^ padding_len

output += bytes([forced_character])

m += 1

return output

Part 2:

The exploiting function goes over the ciphertext, block by block. During the processing of each block, it goes over every byte. This happens with the aid of the modify_block function we saw earlier.

We append the IV to the ciphertext and start verifying the padding of the ciphertext by working with only two blocks at a time, the first one taking place of the (i-1)th block(treated as an IV since only two blocks exist), and the second one taking the place of the ith block(the one we’re trying to decrypt and verify the padding for). The first block is modified so as to yield a valid padding when the next block is decrypted. Since we do not know against which byte would obtain the valid padding, we resort to the brute force approach. We go over all 256 values for the byte in focus, modify the block every time and check if the decrypted plaintext has a valid padding. The moment it does, bingo. That’s our byte. We then move onto the next byte, and then the next block, and then gradually, we have the whole plaintext deciphered right in front of our eyes.

def cbc_padding_attack(ciphertext: bytes, IV: bytes, key: bytes, decryptor: callable) -> bytes:

block_size = len(IV)

# Create ciphertext blocks, with IV prepended to the ciphertexts.

# The prepended IV enables us to decrypt the first block of ciphertext.

plaintext = ""

num_blocks = len(ciphertext)//block_size

ciphertext_blocks = [IV] + [ciphertext[i:i+block_size] for i in range(0, len(ciphertext), block_size)]

# This loop goes over the cipher blocks.

for i in range(1, num_blocks+1):

plain_block = ""

base_block = ciphertext_blocks[i-1]

target_block = ciphertext_blocks[i]

# This loop goes over every byte in a block.

for j in range(1, block_size+1):

possible_last_bytes = []

# This loop goes over all possible values for a byte.

for k in range(256):

mod_block = modify_block(base_block, k, j, plain_block)

check = decryptor(target_block, mod_block, key)

# Make a list of all values that satisfy the padding.

if check == True:

possible_last_bytes += bytes([k])

# If more than one possible bytes have been found, then verify their validity by checking the next byte.

if len(possible_last_bytes) != 1:

for byte in possible_last_bytes:

for k in range(256):

mod_block = modify_block(base_block, k, j+1, chr(byte)+plain_block)

check = decryptor(target_block, mod_block, key)

if check == True:

possible_last_bytes = [byte]

break

# Append the decrypted byte to the plain block.

plain_block = chr(possible_last_bytes[0]) + plain_block

# Append the decrypted block to plaintext.

plaintext += plain_block

return PKCS7_unpad(plaintext.encode())

keysize = AES.block_size

random_key = os.urandom(keysize)

IV = os.urandom(keysize)

selected_string, ciphertext = encryptor(IV, random_key)

plaintext = cbc_padding_attack(ciphertext, IV, random_key, decryptor)

result = base64.b64decode(plaintext).decode("utf-8")

result

"000001With the bass kicked in and the Vega's are pumpin'"

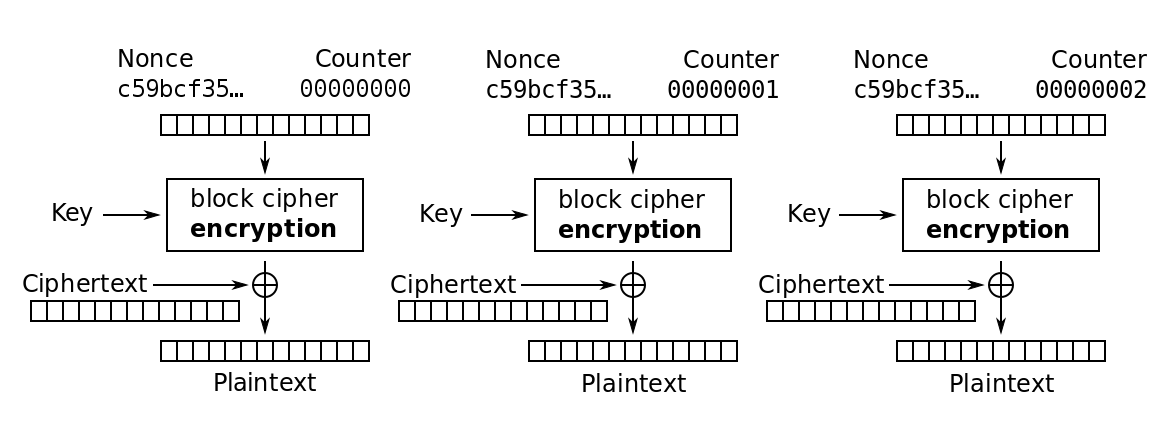

Challenge 18: Implement CTR, the stream cipher mode

The string:

L77na/nrFsKvynd6HzOoG7GHTLXsTVu9qvY/2syLXzhPweyyMTJULu/6/kXX0KSvoOLSFQ== … decrypts to something approximating English in CTR mode, which is an AES block cipher mode that turns AES into a stream cipher, with the following parameters:

** key=YELLOW SUBMARINE

nonce=0

format=64 bit unsigned little endian nonce,

64 bit little endian block count (byte count / 16)

** CTR mode is very simple.

Instead of encrypting the plaintext, CTR mode encrypts a running counter, producing a 16 byte block of keystream, which is XOR’d against the plaintext.

For instance, for the first 16 bytes of a message with these parameters:

keystream = AES(“YELLOW SUBMARINE”,

"\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00")

… for the next 16 bytes:

keystream = AES(“YELLOW SUBMARINE”, “\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00”)

… and then:

keystream = AES(“YELLOW SUBMARINE”,

"\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00")

CTR mode does not require padding; when you run out of plaintext, you just stop XOR’ing keystream and stop generating keystream.

Decryption is identical to encryption. Generate the same keystream, XOR, and recover the plaintext.

Decrypt the string at the top of this function, then use your CTR function to encrypt and decrypt other things.

# Imports

import base64

# Given

b64_string = "L77na/nrFsKvynd6HzOoG7GHTLXsTVu9qvY/2syLXzhPweyyMTJULu/6/kXX0KSvoOLSFQ=="

key = "YELLOW SUBMARINE"

nonce = 0

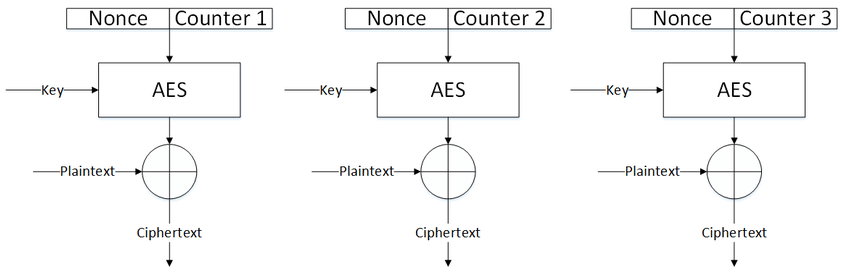

The third AES Mode is the CTR (Counter) Mode. It uses a keystream to encrypt/decrypt, turning block cipher into a stream cipher.

Keystream blocks being generated.

Keystream blocks being generated.

This keystream is generated block at a time, by appending a nonce value, and a counter that is being incremented at every call to it. The counter can be any function which produces a sequence which is guaranteed not to repeat for a long time, although an actual increment-by-one counter is the simplest and most popular.

def CTR_keystream_generator(key: bytes, nonce: int) -> bytes:

"""

Generates keystream based on given key and nonce.

Uses AES ECB Mode to encrypt the nonce+counter block.

"""

counter = 0

# 8 byte because format says 64bit.

nonce_bytes = nonce.to_bytes(8, "little")

while True:

counter_bytes = counter.to_bytes(8, "little")

# Keep getting 16byte block from the encryption function.

keystream_block = AES_ECB_encrypt(nonce_bytes + counter_bytes, key)

yield from keystream_block

counter += 1

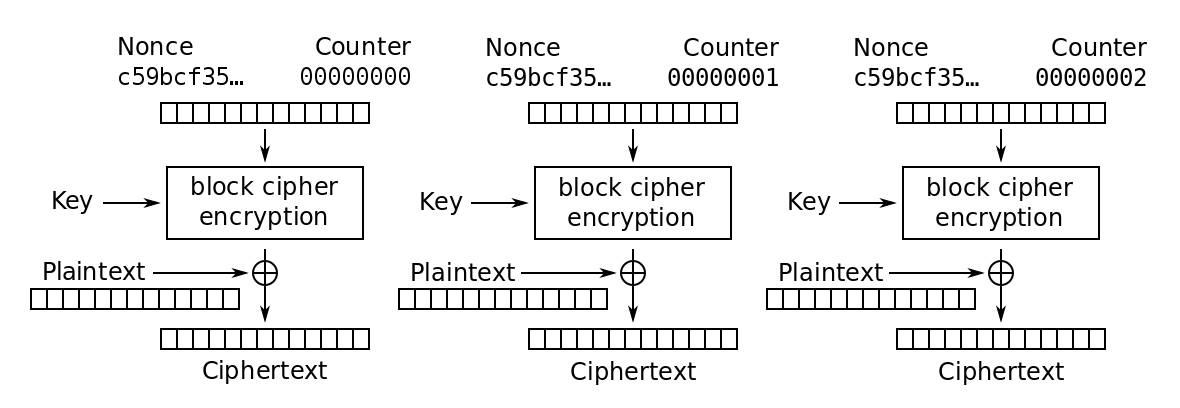

AES CTR Encryption.

AES CTR Encryption.

The encryption process involves encrypting the keystream block with a different block cipher encrypting technique and xoring it with plaintext to generate ciphertext.

AES CTR Decryption.

AES CTR Decryption.

The decryption process can be stated as a mirror of the encryption process. It again encrypts the keystream block with the same block cipher encrypting technique as was used during encryption, and then xoring the ciphertext with it to receive the plaintext back.

It’s clearly a play on one of the crucial properties of the xor operation: it’s reversible.

def CTR(string: bytes, key: bytes, nonce: int) -> bytes:

"""

Encrypts a plaintext with AES CTR Mode.

"""

# Generate the keystream based on key and nonce.

keystream = CTR_keystream_generator(key, nonce)

if len(string) == 0:

return b""

else:

return xor_bytes(string, keystream)

decoded_string = base64.b64decode(b64_string)

byte_text = CTR(decoded_string, key.encode(), 0)

byte_text.decode("utf-8")

"Yo, VIP Let's kick it Ice, Ice, baby Ice, Ice, baby "

I came up with the solution for #19 involving scoring texts based on letter frequency, and it turned out to be the solution for #20 too.

Challenge 19: Break fixed-nonce CTR mode using substitutions

Take your CTR encrypt/decrypt function and fix its nonce value to 0. Generate a random AES key.

In successive encryptions (not in one big running CTR stream), encrypt each line of the base64 decodes of the following, producing multiple independent ciphertexts:

SSBoYXZlIG1ldCB0aGVtIGF0IGNsb3NlIG9mIGRheQ==

Q29taW5nIHdpdGggdml2aWQgZmFjZXM=

RnJvbSBjb3VudGVyIG9yIGRlc2sgYW1vbmcgZ3JleQ==

RWlnaHRlZW50aC1jZW50dXJ5IGhvdXNlcy4=

SSBoYXZlIHBhc3NlZCB3aXRoIGEgbm9kIG9mIHRoZSBoZWFk

T3IgcG9saXRlIG1lYW5pbmdsZXNzIHdvcmRzLA==

T3IgaGF2ZSBsaW5nZXJlZCBhd2hpbGUgYW5kIHNhaWQ=

UG9saXRlIG1lYW5pbmdsZXNzIHdvcmRzLA==

QW5kIHRob3VnaHQgYmVmb3JlIEkgaGFkIGRvbmU=

T2YgYSBtb2NraW5nIHRhbGUgb3IgYSBnaWJl

VG8gcGxlYXNlIGEgY29tcGFuaW9u

QXJvdW5kIHRoZSBmaXJlIGF0IHRoZSBjbHViLA==

QmVpbmcgY2VydGFpbiB0aGF0IHRoZXkgYW5kIEk=

QnV0IGxpdmVkIHdoZXJlIG1vdGxleSBpcyB3b3JuOg==

QWxsIGNoYW5nZWQsIGNoYW5nZWQgdXR0ZXJseTo=

QSB0ZXJyaWJsZSBiZWF1dHkgaXMgYm9ybi4=

VGhhdCB3b21hbidzIGRheXMgd2VyZSBzcGVudA==

SW4gaWdub3JhbnQgZ29vZCB3aWxsLA==

SGVyIG5pZ2h0cyBpbiBhcmd1bWVudA==

VW50aWwgaGVyIHZvaWNlIGdyZXcgc2hyaWxsLg==

V2hhdCB2b2ljZSBtb3JlIHN3ZWV0IHRoYW4gaGVycw==

V2hlbiB5b3VuZyBhbmQgYmVhdXRpZnVsLA==

U2hlIHJvZGUgdG8gaGFycmllcnM/

VGhpcyBtYW4gaGFkIGtlcHQgYSBzY2hvb2w=

QW5kIHJvZGUgb3VyIHdpbmdlZCBob3JzZS4=

VGhpcyBvdGhlciBoaXMgaGVscGVyIGFuZCBmcmllbmQ=

V2FzIGNvbWluZyBpbnRvIGhpcyBmb3JjZTs=

SGUgbWlnaHQgaGF2ZSB3b24gZmFtZSBpbiB0aGUgZW5kLA==

U28gc2Vuc2l0aXZlIGhpcyBuYXR1cmUgc2VlbWVkLA==

U28gZGFyaW5nIGFuZCBzd2VldCBoaXMgdGhvdWdodC4=

VGhpcyBvdGhlciBtYW4gSSBoYWQgZHJlYW1lZA==

QSBkcnVua2VuLCB2YWluLWdsb3Jpb3VzIGxvdXQu

SGUgaGFkIGRvbmUgbW9zdCBiaXR0ZXIgd3Jvbmc=

VG8gc29tZSB3aG8gYXJlIG5lYXIgbXkgaGVhcnQs

WWV0IEkgbnVtYmVyIGhpbSBpbiB0aGUgc29uZzs=

SGUsIHRvbywgaGFzIHJlc2lnbmVkIGhpcyBwYXJ0

SW4gdGhlIGNhc3VhbCBjb21lZHk7

SGUsIHRvbywgaGFzIGJlZW4gY2hhbmdlZCBpbiBoaXMgdHVybiw=

VHJhbnNmb3JtZWQgdXR0ZXJseTo=

QSB0ZXJyaWJsZSBiZWF1dHkgaXMgYm9ybi4=

(This should produce 40 short CTR-encrypted ciphertexts).

Because the CTR nonce wasn’t randomized for each encryption, each ciphertext has been encrypted against the same keystream. This is very bad.

Understanding that, like most stream ciphers (including RC4, and obviously any block cipher run in CTR mode), the actual “encryption” of a byte of data boils down to a single XOR operation, it should be plain that:

CIPHERTEXT-BYTE XOR PLAINTEXT-BYTE = KEYSTREAM-BYTE

And since the keystream is the same for every ciphertext:

CIPHERTEXT-BYTE XOR KEYSTREAM-BYTE = PLAINTEXT-BYTE (ie, “you don’t say!”)

Attack this cryptosystem piecemeal: guess letters, use expected English language frequence to validate guesses, catch common English trigrams, and so on.

and

Challenge 20: Break fixed-nonce CTR statistically

In this file find a similar set of Base64’d plaintext. Do with them exactly what you did with the first, but solve the problem differently.

Instead of making spot guesses at to known plaintext, treat the collection of ciphertexts the same way you would repeating-key XOR.

Obviously, CTR encryption appears different from repeated-key XOR, but with a fixed nonce they are effectively the same thing.

To exploit this: take your collection of ciphertexts and truncate them to a common length (the length of the smallest ciphertext will work).

Solve the resulting concatenation of ciphertexts as if for repeating- key XOR, with a key size of the length of the ciphertext you XOR’d.

# Imports

import os

import base64

# Given

b64_strings = open("20.txt").readlines()

nonce = 0

random_key = os.urandom(16)

decoded_strings = [base64.b64decode(line.strip()) for line in b64_strings]

ciphertext_list = [CTR(string, random_key, nonce) for string in decoded_strings]

min_ciphertext_length = min(map(len, ciphertext_list))

The thing to note here is the fact that the same keystream is used to encrypt all the strings provided in the file. Therefore, if we stack all the ciphertext strings one on top of the other, it becomes clear that all the Nth byte in each of the ciphertext strings have been encrypted by the Nth byte of the keystream. Therefore, it can be considered to be a case of single-byte xor.

The function extends the idea from #6: create blocks of the bytes at same indices from all the ciphertext strings, and then solve them based on the score from letters.

columns = []

for i in range(min_ciphertext_length):

line = b""

for cipher in ciphertext_list:

line += cipher[i].to_bytes(1, "big")

result = single_byte_xor_score(line)

columns.append(result["message"])

message = ""

for i in range(min_ciphertext_length):

for c in columns:

message += c[i]

message

'N\'m rated "R"...this is a warning, ya better void / PDuz I came back to attack others in spite- / Strike lEut don\'t be afraid in the dark, in a park / Not a sc^a tremble like a alcoholic, muscles tighten up / WhaTuddenly you feel like your in a horror flick / You gJusic\'s the clue, when I come your warned / ApocalypsOaven\'t you ever heard of a MC-murderer? / This is thCeath wish, so come on, step to this / Hysterical ideAriday the thirteenth, walking down Elm Street / You Shis is off limits, so your visions are blurry / All Serror in the styles, never error-files / Indeed I\'m Aor those that oppose to be level or next to this / IPorse than a nightmare, you don\'t have to sleep a winAlashbacks interfere, ya start to hear: / The R-A-K-IShen the beat is hysterical / That makes Eric go get Toon the lyrical format is superior / Faces of death JC\'s decaying, cuz they never stayed / The scene of aShe fiend of a rhyme on the mic that you know / It\'s Jelodies-unmakable, pattern-unescapable / A horn if wN bless the child, the earth, the gods and bomb the rOazardous to your health so be friendly / A matter ofThake \'till your clear, make it disappear, make the nNf not, my soul\'ll release! / The scene is recreated,Duz your about to see a disastrous sight / A performaKyrics of fury! A fearified freestyle! / The "R" is iJake sure the system\'s loud when I mention / Phrases ^ou want to hear some sounds that not only pounds butShen nonchalantly tell you what it mean to me / StricFnd I don\'t care if the whole crowd\'s a witness! / I\'Wrogram into the speed of the rhyme, prepare to startJusical madness MC ever made, see it\'s / Now an emergHpen your mind, you will find every word\'ll be / FuriEattle\'s tempting...whatever suits ya! / For words th^ou think you\'re ruffer, then suffer the consequencesN wake ya with hundreds of thousands of volts / Mic-tIovocain ease the pain it might save him / If not, Er^o Rakim, what\'s up? / Yo, I\'m doing the knowledge, EPell, check this out, since Norby Walters is our agenLara Lewis is our agent, word up / Zakia and 4th and Hkay, so who we rollin\' with then? We rollin\' with RuDheck this out, since we talking over / This def beatN wanna hear some of them def rhymes, you know what IShinkin\' of a master plan / \'Cuz ain\'t nuthin\' but swTo I dig into my pocket, all my money is spent / So ITo I start my mission, leave my residence / Thinkin\' N need money, I used to be a stick-up kid / So I thinN used to roll up, this is a hold up, ain\'t nuthin\' fEut now I learned to earn \'cuz I\'m righteous / I feelTearch for a nine to five, if I strive / Then maybe ITo I walk up the street whistlin\' this / Feelin\' out F pen and a paper, a stereo, a tape of / Me and Eric Aish, which is my favorite dish / But without no mone Cuz I don\'t like to dream about gettin\' paid / So I '

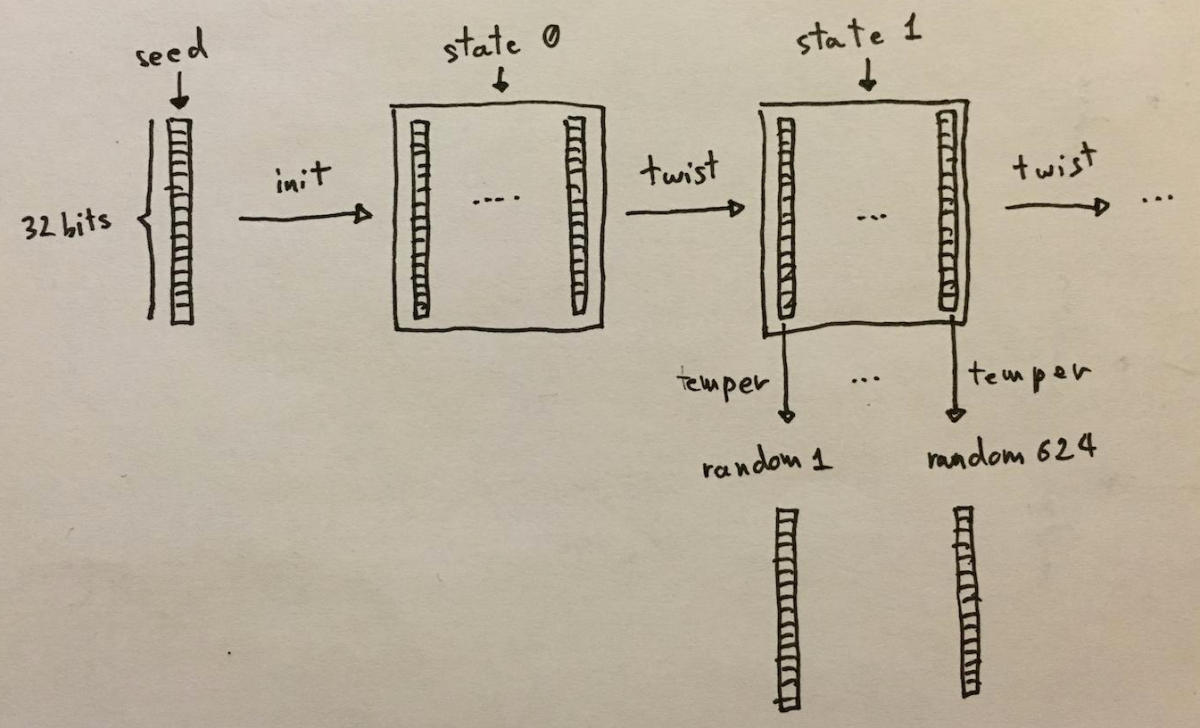

Challenge 21: Implement the MT19937 Mersenne Twister RNG

You can get the psuedocode for this from Wikipedia.

If you’re writing in Python, Ruby, or (gah) PHP, your language is probably already giving you MT19937 as “rand()”; don’t use rand(). Write the RNG yourself.

# Imports

import time

The Mersenne Twister is a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG). It is by far the most widely used general-purpose PRNG. It’s name derives from the fact that its period length is chosen to be a Mersenne prime.

The implementation is derived from the pseudo-code on Wikipedia. Any of the above links can be used to study more on the topic.

Mersenne Twister.

Mersenne Twister.

def get_lowest_bits(n: int, number_of_bits: int) -> int:

"""

Returns the lowest "number_of_bits" bits of n.

"""

mask = (1 << number_of_bits) - 1

return n &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; mask

class MT19937:

"""

This implementation resembles the one of the Wikipedia pseudo-code.

"""

W, N, M, R = 32, 624, 397, 31

A = 0x9908B0DF

U, D = 11, 0xFFFFFFFF

S, B = 7, 0x9D2C5680

T, C = 15, 0xEFC60000

L = 18

F = 1812433253

LOWER_MASK = (1 << R) - 1

UPPER_MASK = get_lowest_bits(not LOWER_MASK, W)

def __init__(self: object, seed: int):

self.mt = []

self.index = self.N

self.mt.append(seed)

for i in range(1, self.index):

self.mt.append(get_lowest_bits(self.F * (self.mt[i - 1] ^ (self.mt[i - 1] >> (self.W - 2))) + i, self.W))

def extract_number(self: object) -> int:

"""

Extracts the new random number.

"""

if self.index >= self.N:

self.twist()

y = self.mt[self.index]

y ^= (y >> self.U) &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; self.D

y ^= (y << self.S) &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; self.B

y ^= (y << self.T) &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; self.C

y ^= (y >> self.L)

self.index += 1

return get_lowest_bits(y, self.W)

def twist(self: object):

"""

Performs the twisting part of the encryption.

"""

for i in range(self.N):

x = (self.mt[i] &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; self.UPPER_MASK) + (self.mt[(i + 1) % self.N] &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; self.LOWER_MASK)

x_a = x >> 1

if x % 2 != 0:

x_a ^= self.A

self.mt[i] = self.mt[(i + self.M) % self.N] ^ x_a

self.index = 0

# Check if the numbers look random

for i in range(10):

print(MT19937(i).extract_number())

2357136044

1791095845

1872583848

2365658986

4153361530

953453411

3834805130

327741615

3751350723

44556670

Challenge 22: Crack an MT19937 seed

Make sure your MT19937 accepts an integer seed value. Test it (verify that you’re getting the same sequence of outputs given a seed).

Write a routine that performs the following operation:

- Wait a random number of seconds between, I don’t know, 40 and 1000.

- Seeds the RNG with the current Unix timestamp.

- Waits a random number of seconds again.

- Returns the first 32 bit output of the RNG.

You get the idea. Go get coffee while it runs. Or just simulate the passage of time, although you’re missing some of the fun of this exercise if you do that.

From the 32 bit RNG output, discover the seed.

# Imports

import time

import random

The point of this function is to generate a time-based seed, but to throw off the attacker by executing a sleep for a random time before generating the seed and again for a random time after generating it.

def MT19937_timestamp_seed() -> (int, int):

"""

Generates a timestamp based seed for MT19937.

"""

# Sleeps for a random time to generate a random seed.

time.sleep(random.randint(40, 100))

seed = int(time.time())

# Initialises the object with the generated seed.

mt_rng = MT19937(seed)

# Sleep for a random time to throw off the attacker.

time.sleep(random.randint(40, 100))

return mt_rng.extract_number(), seed

We brute force the seed value by approximating the maximum time spent between generation of the seed and the value returned to us (I took it to be 200),

def break_MT19937_seed(rng_function: callable) -> int:

"""

Breaks the MT19937 seed value.

"""

random_number, real_seed = rng_function()

# Note current time to start backtracking by the millisecond.

now = int(time.time())

# Assuming 200 seconds to be the maximum time between generation of seed and us receiving it.

before = now - 200

# Brtue force with the value of seed between the set time frame.

for seed in range(before, now):

rng = MT19937(seed)

number = rng.extract_number()

if number == random_number:

return seed

number = break_MT19937_seed(MT19937_timestamp_seed)

Challenge 23: Clone an MT19937 RNG from its output

The internal state of MT19937 consists of 624 32 bit integers.

For each batch of 624 outputs, MT permutes that internal state. By permuting state regularly, MT19937 achieves a period of 2**19937, which is Big.

Each time MT19937 is tapped, an element of its internal state is subjected to a tempering function that diffuses bits through the result.

The tempering function is invertible; you can write an “untemper” function that takes an MT19937 output and transforms it back into the corresponding element of the MT19937 state array.

To invert the temper transform, apply the inverse of each of the operations in the temper transform in reverse order. There are two kinds of operations in the temper transform each applied twice; one is an XOR against a right-shifted value, and the other is an XOR against a left-shifted value AND’d with a magic number. So you’ll need code to invert the “right” and the “left” operation.

Once you have “untemper” working, create a new MT19937 generator, tap it for 624 outputs, untemper each of them to recreate the state of the generator, and splice that state into a new instance of the MT19937 generator.

The new “spliced” generator should predict the values of the original.

# Imports

import time

import random

The major ground work to be done here is to reverse the temper function, that is, to create an “untempering” function. Since the question tells us that the tempering function is invertible, writing such a function is possible. Have a go at it.

def int_to_bit_list(x: int) -> list:

"""

Convert an integer to it's binary form, and return the bits in a list.

"""

return [int(b) for b in "{:032b}".format(x)]

def bit_list_to_int(l: list) -> int:

"""

Receive a list of bits and convert it into an integer.

"""

return int(''.join(str(x) for x in l), base=2)

def invert_shift_mask_xor(y: int, direction: str, shift: int, mask=0xFFFFFFFF) -> int:

"""

Shift, mask and xor the given integer in the specified direction with the passed mask.

"""

y = int_to_bit_list(y)

mask = int_to_bit_list(mask)

if direction == "left":

y.reverse()

mask.reverse()

else:

assert direction == "right"

x = [None]*32

for n in range(32):

if n < shift:

x[n] = y[n]

else:

x[n] = y[n] ^ (mask[n] &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; x[n-shift])

if direction == 'left':

x.reverse()

return bit_list_to_int(x)

def untemper(y: int) -> int:

"""

Reverses the temper part of the Mersenne Twister.

"""

(w, n, m, r) = (32, 624, 397, 31)

a = 0x9908B0DF

(u, d) = (11, 0xFFFFFFFF)

(s, b) = (7, 0x9D2C5680)

(t, c) = (15, 0xEFC60000)

l = 18

f = 1812433253

xx = y

xx = invert_shift_mask_xor(xx, direction='right', shift=l)

xx = invert_shift_mask_xor(xx, direction='left', shift=t, mask=c)

xx = invert_shift_mask_xor(xx, direction='left', shift=s, mask=b)

xx = invert_shift_mask_xor(xx, direction='right', shift=u, mask=d)

return xx

Once the “untempering” function is setup, the MT19937 generator can be tapped into for it’s current state, saved in the form of 624 outputs. This state can be used to initialise a new generatorm which can therefore predict the outputs of the current one, since it’s figuratively stepping in the original generator’s shoes by replicating it’s state.

def get_cloned_rng(original_rng: callable) -> callable:

"""Taps the given rng for 624 outputs, untempers each of them to recreate the state of the generator,

and splices that state into a new "cloned" instance of the MT19937 generator.

"""

mt = []

# Recreate the state mt of original_rng.

for i in range(MT19937.N):

mt.append(untemper(original_rng.extract_number()))

# Create a new generator and set it to have the same state.

cloned_rng = MT19937(0)

cloned_rng.mt = mt

return cloned_rng

seed = random.randint(0, 2**32 - 1)

rng = MT19937(seed)

cloned_rng = get_cloned_rng(rng)

# Check that the two PRNGs produce the same output.

for i in range(99):

if rng.extract_number() != cloned_rng.extract_number():

test(rng.extract_number() == print(cloned_rng.extract_number()))

Challenge 24: Create the MT19937 stream cipher and break it

You can create a trivial stream cipher out of any PRNG; use it to generate a sequence of 8 bit outputs and call those outputs a keystream. XOR each byte of plaintext with each successive byte of keystream.

Write the function that does this for MT19937 using a 16-bit seed. Verify that you can encrypt and decrypt properly. This code should look similar to your CTR code.

Use your function to encrypt a known plaintext (say, 14 consecutive ‘A’ characters) prefixed by a random number of random characters.

From the ciphertext, recover the “key” (the 16 bit seed).

Use the same idea to generate a random “password reset token” using MT19937 seeded from the current time.

Write a function to check if any given password token is actually the product of an MT19937 PRNG seeded with the current time.

# Imports

import os

import time

import math

import random

The function mentioned in question to generate a keystream out of a 16-bit seed fed MT19937 generator.

def MT19937_keystream_generator(seed: int) -> bytes:

"""

Generate keystream for MT19937

"""

# Verify that the seed is atmost 16 bit long.

assert math.log2(seed) <= 16

prng = MT19937(seed)

while True:

number = prng.extract_number()

yield from number.to_bytes(4, "big")

The function to encrypt a given string via a MT19937 generated keystream.

def MT19937_CTR(string: str, seed: int) -> bytes:

"""

Encrypts a plaintext with MT19937 CTR Mode.

"""

# Verify that the seed is an integer.

assert isinstance(seed, int)

keystream = MT19937_keystream_generator(seed)

if len(string) == 0:

return b""

else:

return bytes([(b1 ^ b2) for b1, b2 in zip(string, keystream)])

plaintext = "Hello World!"

# Append random characters before plainttext.

string = b""

for _ in range(random.randint(0, 10)):

i = random.randint(33, 126)

string += chr(i).encode()

string += plaintext.encode()

seed = random.randint(1, 2**16)

print("> Seed value coded to be", seed)

cipher_bytes = MT19937_CTR(string, seed)

deciphered_bytes = MT19937_CTR(cipher_bytes, seed)

# Verify if it can be decrypted.

assert string == deciphered_bytes

# A 16 bit key makes it easy to brute force the key.

for seed in range(1, 2**16):

deciphered_bytes = MT19937_CTR(cipher_bytes, seed)

try:

assert string == deciphered_bytes

print("> Brute force successful.\nSeed:", seed)

test(True)

break

except AssertionError:

continue

> Seed value coded to be 41129

> Brute force successful.

Seed: 41129