7 minutes

Anatomy of a Binary

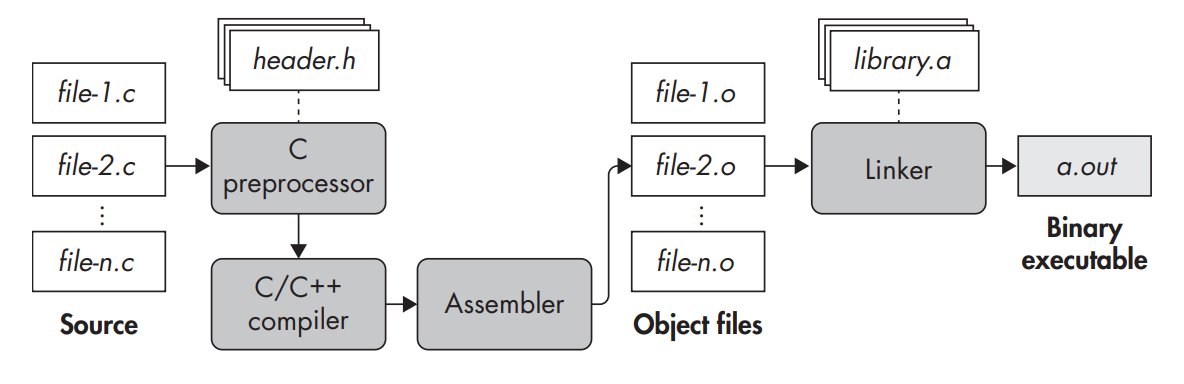

The C Compilation Process

- Compilation is the process of translating human readable source code into machine code that the processor can execute.

- Binary Code is the machine code that systems execute.

- Binary Executable Files, or Binaries, store the executable binary program, that is, the code and data belonging to each program.

#include <stdio.h>

#define FORMAT_STRING "%s"

#define MESSAGE "Hello, world!\n"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf(FORMAT_STRING, MESSAGE);

return 0;

}

The C Compilation Process.

The C Compilation Process.

Preprocessor

- Expands macros(#define) and #include directives into pure C code.

- Every #include directive, the header is copied in its entirety.

- Every #define directive is fully expanded everywhere it is used.

$ gcc -E -P compilation_example.c

typedef long unsigned int size_t;

typedef unsigned char __u_char;

typedef unsigned short int __u_short;

typedef unsigned int __u_int;

typedef unsigned long int __u_long;

/* ... */

extern int sys_nerr;

extern const char *const sys_errlist[];

extern int fileno (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__)) ;

extern int fileno_unlocked (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__)) ;

extern FILE *popen (const char *__command, const char *__modes) ;

extern int pclose (FILE *__stream);

extern char *ctermid (char *__s) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__));

extern void flockfile (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__));

extern int ftrylockfile (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__)) ;

extern void funlockfile (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__));

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("%s", "Hello, world!\n");

return 0;

}

Compiler

- Takes the preprocessed code and translates it into assembly language.

- Most compilers also perform heavy optimization in this phase, typically configurable as an optimization level through command line switches such as options -O0 through -O3 in gcc.

- Compilation phase produce assembly language and not machine code because it’s better to instead have a language dedicated compiler that emits generic assembly code and have a single universal assembler that can handle the final translation of assembly to machine code for every language.

- Output of the compilation phase is an assembly file, which is in reasonably human-readable form, with symbolic information intact.

- All references are purely symbolic.

- Compilers use an optimization called dead code elimination to find instances of code that can never be reached in practice so that they can omit such useless code in the compiled binary.

- Each source code file corresponds to one assembly file.

- Takes .c file as input and produces .s assembly file.

$ gcc -S -masm=intel compilation_example.c

$ cat compilation_example.s

.file "compilation_example.c"

.intel_syntax noprefix

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Hello, world!"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

push rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 6, -16

mov rbp, rsp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 6

sub rsp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], edi

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-16], rsi

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

call puts

mov eax, 0

leave

.cfi_def_cfa 7, 8

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu 5.4.0-6ubuntu1~16.04.4) 5.4.0 20160609"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

Assembler

- Takes assembly files as input and produces object files (modules) as output.

- Each assembly file corresponds to one object file.

- Object files contain machine instructions that are in principle executable by the processor.

- Takes .c file as input and produces .o object file.

$ gcc -c compilation_example.c

$ file compilation_example.o

compilation_example.o: ELF 64-bit LSB relocatable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), not stripped

- Relocatable Files can be placed at any position in the memory. It’s an indication of the file being an object/module. It’s important since object files are compiled independently from each other and assembler has no way to know the order to link them into. Making them relocatable allows them to be linked in any order to construct a complete executable.

- Object files contain Relocation Symbols that specify how function and variable references must be resolved. References that rely on a relocation symbol, such as an object file referencing one if its own functions/variables by absolute address, are known as Symbolic References.

Linker

- Links together all object files together to form a single coherent executable, which will be loaded at a particular memory address.

- Can incorporate an additional optimization pass called link-time optimization (LTO).

- Linker resolves all symbolic references now that the arrangement of modules is known after linking.

- Static libraries are merged into the executable allowing all references to be resolved entirely. Symbolic references to dynamic libraries are left unresolved even in the final executable (will be resolved during execution).

$ gcc compilation_example.c

$ file a.out

a.out: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=d0e23ea731bce9de65619cadd58b14ecd8c015c7, not stripped

$ ./a.out

Hello, world!

Symbols and Stripped Binaries

- Symbols keep track of symbolic names and records which binary code and data correspond to. They provide a mapping from high-level names to address and size. This information is required by linker.

$ readelf --syms a.out

Symbol table '.dynsym' contains 4 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT UND puts@GLIBC_2.2.5 (2)

2: 0000000000000000 0 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT UND __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5 (2)

3: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE WEAK DEFAULT UND __gmon_start__

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 67 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

...

56: 0000000000601030 0 OBJECT GLOBAL HIDDEN 25 __dso_handle

57: 00000000004005d0 4 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 16 _IO_stdin_used

58: 0000000000400550 101 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 __libc_csu_init

59: 0000000000601040 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT 26 _end

60: 0000000000400430 42 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 _start

61: 0000000000601038 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT 26 __bss_start

62: 0000000000400526 32 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 main

63: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE WEAK DEFAULT UND _Jv_RegisterClasses

64: 0000000000601038 0 OBJECT GLOBAL HIDDEN 25 __TMC_END__

65: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE WEAK DEFAULT UND _ITM_registerTMCloneTable

66: 00000000004003c8 0 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 11 _init

- Focusing on ‘main’, we can see it will be loaded at address ‘0x400526’ when the binary is loaded into memory and it’s size is 32bytes. ‘FUNC’ shows that we are dealing with a function symbol.

- Debugging symbols are typically generated in DWARF format for ELF binaries (usually embedded inside) and PDB (Microsoft Portable Debugging) format for PE binaries (separate file).

Stripped Binaries

- On stripping a binary, only a few symbols are left in the .dynsym symbol table. These are used to resolve dynamic dependencies (such as references to dynamic libraries) when the binary is loaded into memory, but they’re not much use when disassembling.

$ strip --strip-all a.out

$ file a.out

a.out: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=d0e23ea731bce9de65619cadd58b14ecd8c015c7, stripped

$ readelf --syms a.out

Symbol table '.dynsym' contains 4 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT UND puts@GLIBC_2.2.5 (2)

2: 0000000000000000 0 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT UND __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5 (2)

3: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE WEAK DEFAULT UND __gmon_start__

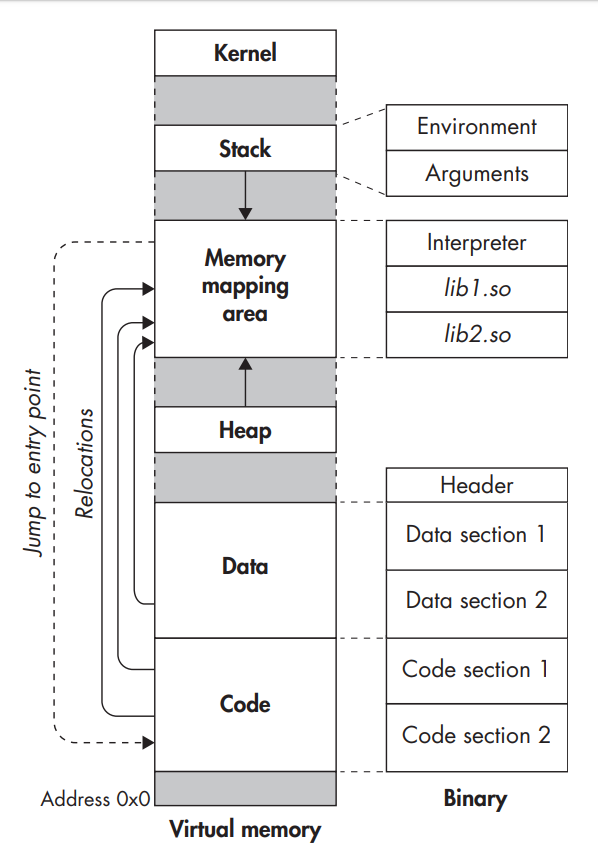

Loading and Executing a Binary

Loading an ELF binary on a Linux-based system.

Loading an ELF binary on a Linux-based system.

- A binary’s representation in memory does not necessarily correspond one-to-one with its on-disk representation, like collapsing a string of zeros to a single one to save space, and re-expand while loading into the memory.

- A new process is setup for the program to run in, including a virtual address space. Subsequently, the operating system maps an interpreter into the process’s virtual memory to load the binary and perform the necessary relocations. On Linux, the interpreter is typically a shared library called ld-linux.so. On Windows, the interpreter functionality is implemented as part of ntdll.dll. After loading the interpreter, the kernel transfers control to it, and the interpreter begins its work in user space.

- The interpreter then maps the dynamic libraries required into the virtual address space (using mmap or an equivalent function) and then resolves any relocations left in the binary’s code sections to fill in the correct addresses for references to the dynamic libraries.

- Linux ELF binaries come with a special section called .interp that specifies the path to the interpreter.

$ readelf -p .interp a.out

String dump of section '.interp':

[0] /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

Citation: Practical Binary Analysis.